- Y Diweddaraf sydd Ar Gael (Diwygiedig)

- Gwreiddiol (Fel y’i mabwysiadwyd gan yr UE)

Commission Decision (EU) 2015/801Dangos y teitl llawn

Commission Decision (EU) 2015/801 of 20 May 2015 on reference document on best environmental management practice, sector environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence for the retail trade sector under Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS) (notified under document C(2015) 3234) (Text with EEA relevance)

You are here:

- Penderfyniadau yn deillio o’r UE

- 2015 No. 801

- Whole Decision

- Blaenorol

- Nesaf

Rhagor o Adnoddau

When the UK left the EU, legislation.gov.uk published EU legislation that had been published by the EU up to IP completion day (31 December 2020 11.00 p.m.). On legislation.gov.uk, these items of legislation are kept up-to-date with any amendments made by the UK since then.

Mae hon yn eitem o ddeddfwriaeth sy’n deillio o’r UE

Mae unrhyw newidiadau sydd wedi cael eu gwneud yn barod gan y tîm yn ymddangos yn y cynnwys a chyfeirir atynt gydag anodiadau.Ar ôl y diwrnod ymadael bydd tair fersiwn o’r ddeddfwriaeth yma i’w gwirio at ddibenion gwahanol. Y fersiwn legislation.gov.uk yw’r fersiwn sy’n weithredol yn y Deyrnas Unedig. Y Fersiwn UE sydd ar EUR-lex ar hyn o bryd yw’r fersiwn sy’n weithredol yn yr UE h.y. efallai y bydd arnoch angen y fersiwn hon os byddwch yn gweithredu busnes yn yr UE. EUR-Lex Y fersiwn yn yr archif ar y we yw’r fersiwn swyddogol o’r ddeddfwriaeth fel yr oedd ar y diwrnod ymadael cyn cael ei chyhoeddi ar legislation.gov.uk ac unrhyw newidiadau ac effeithiau a weithredwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig wedyn. Mae’r archif ar y we hefyd yn cynnwys cyfraith achos a ffurfiau mewn ieithoedd eraill o EUR-Lex. The EU Exit Web Archive legislation_originated_from_EU_p3

Status:

EU_status_warning_original_version

This legislation may since have been updated - see the latest available (revised) version

Commission Decision (EU) 2015/801

of 20 May 2015

on reference document on best environmental management practice, sector environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence for the retail trade sector under Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS)

(notified under document C(2015) 3234)

(Text with EEA relevance)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS), repealing Regulation (EC) No 761/2001 and Commission Decisions 2001/681/EC and 2006/193/EC(1), and in particular Article 46(1) thereof,

Whereas:

(1) Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 establishes an obligation for the Commission to develop sectoral reference documents in consultation with Member States and other stakeholders. These Sectoral Reference Documents must include best environmental management practice, environmental performance indicators for specific sectors and where appropriate benchmarks of excellence and rating systems identifying environmental performance levels.

(2) Communication from the Commission — Establishment of the working plan setting out an indicative list of sectors for the adoption of sectoral and cross-sectoral reference documents, under Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009, of 25 November 2009, on the voluntary participation of organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS)(2) — sets out a working plan and an indicative list of priority sectors for the adoption of sectoral and cross-sectoral reference documents including the wholesale and retail trade sector.

(3) Sectoral reference documents for specific sectors, including best environmental management practices, environmental performance indicators, and where appropriate, benchmarks of excellence and rating systems identifying environmental performance levels, are necessary to help organisations to better focus on the most important environmental aspects in a given sector.

(4) The measures provided for in this Decision are in accordance with the opinion of the Committee established pursuant to Article 49 of Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009,

HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION:

Article 1

The sectoral reference document on best environmental management practice, sector environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence for the retail trade sector is set out in Annex.

Article 2

It is an obligation for an EMAS registered organisation in the retail trade sector to demonstrate in the environmental statement how the described Best Environmental Management Practices and Benchmarks of Excellence from the sectoral reference document have been used to identify measures and actions, and possibly to set priorities for improving their environmental performance.

Article 3

Meeting the benchmarks of excellence identified in the sectoral reference document is not mandatory for EMAS registered organisations since the voluntary character of EMAS leaves the assessment of the feasibility of the benchmarks, in terms of costs and benefits, to the organisations themselves.

Article 4

This Decision is addressed to the Member States.

Done at Brussels, 20 May 2015.

For the Commission

Karmenu Vella

Member of the Commission

ANNEX

1.INTRODUCTION

This document is the first Sectoral Reference Document (SRD) according to Article 46 of Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 on the voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS). With a view to facilitating the understanding of this SRD, this introduction provides an outline of its legal background and its use.

The SRD is based on a detailed scientific and policy report(3) developed by the Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS), one of the seven institutes of the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC).

Relevant legal background

The Community Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) was introduced in 1993 for voluntary participation by organisations, by Council Regulation (EEC) No 1836/93(4). Subsequently, EMAS has undergone two major revisions:

Regulation (EC) No 761/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council(5),

Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009.

An important new element of the latest revision, which came into force on 11 January 2010, is the development of sectoral reference documents (SRDs) reflecting best environmental management practice for specific sectors, introduced by Article 46 of Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009. They include best environmental management practices (BEMPs), environmental performance indicators for specific sectors and, where appropriate, benchmarks of excellence and rating systems identifying performance levels.

How to understand and to use this document

The Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) is a scheme for voluntary participation by organisations which commit to continuous environmental improvement. Within this framework, the present Sectoral Reference Document (SRD) provides sector-specific guidance to the retail trade sector and points out a number of options for improvement and best practices. The SRD is aimed at helping and supporting all organisations which intend to improve their environmental performance by providing ideas and inspiration as well as practical and technical guidance.

The SRD primarily addresses organisations that are already EMAS-registered, secondly organisations that consider registering with EMAS in the future, and thirdly also those which have implemented another environmental management system or those without a formal environmental management system wishing to learn more about best environmental management practices in order to improve their environmental performance. Consequently, the objective of this document is to support all organisations and actors in the retail trade sector to focus on relevant environmental aspects, both direct and indirect, and to find information on best practices, as well as appropriate sector specific environmental performance indicators to measure their environmental performance, and benchmarks of excellence.

According to Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009, EMAS-registered organisations are required to prepare an environmental statement (Article 4(1)(d)). When assessing the environmental performance, the relevant SRD shall be taken into account. Commission Decision 2013/131/EU(6) establishing the user's guide setting out the steps needed to participate in EMAS (the ‘EMAS User's Guide’) also refers to the legal character of the EMAS Sectoral Reference Documents. Both the EMAS User's Guide and this decision state that it is an obligation for an EMAS registered organisation to clarify in the environmental statement how the SRD, when available, was taken into account; i.e. how the SRD has been used to identify measures and actions, and possibly to set priorities, to (further) improve the environmental performance. In addition, this decision also states that meeting the identified benchmarks of excellence is not mandatory because the voluntary character of EMAS leaves the assessment of the feasibility of the benchmarks, in terms of costs and benefits, to the organisations themselves.

The information in this document is based on the direct data supplied by stakeholders themselves followed by a subsequent analysis of the European Commission's Joint Research Centre. A Technical Working Group, comprising experts and stakeholders of the sector, applied their expert judgement together with the European Commission's Joint Research Centre and ultimately agreed and approved the described benchmarks. This means that the information provided on the appropriate sector specific environmental performance indicators and the benchmarks of excellence in this document correspond to the levels of environmental performance that can be achieved by the best performing organisations from the sector. With respect to the environmental statement, Article 4(1)(d) of Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 refers to ANNEX IV to that Regulation, where it is stated that the environmental statement shall also contain reporting on the core indicators and on other relevant existing environmental performance indicators. The so-called ‘other relevant existing environmental performance indicators’ (ANNEX IV(C)(3)) relate to the more specific environmental aspects as identified in the environmental statement and shall be reported in addition to the core indicators. For this purpose, the SRD shall be taken into account also (ANNEX IV(C)(3)). Where justified on technical grounds, an organisation may conclude that one or more of the EMAS core indicators and one or more of the sector-specific indicators presented in the SRD are not relevant for them and may not report on them. For instance, for a non-food retailer, it is not necessary to report on energy efficiency indicators for commercial food refrigeration as this is not relevant for them. When choosing the relevant indicators, it should be considered that some indicators are closely linked to the implementation of certain best practices. Therefore, their applicability is limited to organisations implementing such best environmental management practices. However, if a best environmental management practice is suitable to an organisation, even if not applied, it is recommendable that the organisation report on the associated indicator, at least, to establish a comparable baseline.

The indicators presented were selected as those most commonly used by exemplary organisations within the sector. Organisations may check which of the selected environmental performance indicators (or appropriate alternatives) are the most suitable in each case.

EMAS environmental verifiers shall check if and how the SRD was taken into account by the organisation when preparing its environmental statement (Article 18(5)(d) of Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009). This means that when undertaking their activities, accredited environmental verifiers will need evidence from the organisation on how the SRD has been taken into account. They shall not check compliance with the described benchmarks of excellence, but they shall verify evidence on how the SRD was used as a guide to identify proper voluntary measures that the organisation can implement to improve its environmental performance.

EMAS registration is an ongoing process. This means that every time an organisation plans to improve its environmental performance (and reviews its environmental performance) it shall consult the SRD on specific topics to provide inspiration about which issues to tackle next in a step-wise approach.

Structure of the Sectoral Reference Document

This document consists of four chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the EMAS legal background and describes how to use this document, while Chapter 2 defines the scope of this SRD. Chapter 3 briefly describes the different best environmental management practices (BEMPs) together with information on their applicability, mainly with respect to new and existing installations and/or new and existing stores as well as to SMEs. For each BEMP, the suitable environmental performance indicators and the related benchmarks of excellence are also given. For each of the different measures and techniques outlined, more than one environmental performance indicator is mentioned to reflect the fact that different indicators are used in practice.

Finally, Chapter 4 presents a comprehensive table with the most relevant environmental performance indicators, associated explanations and related benchmarks of excellence.

2.SCOPE

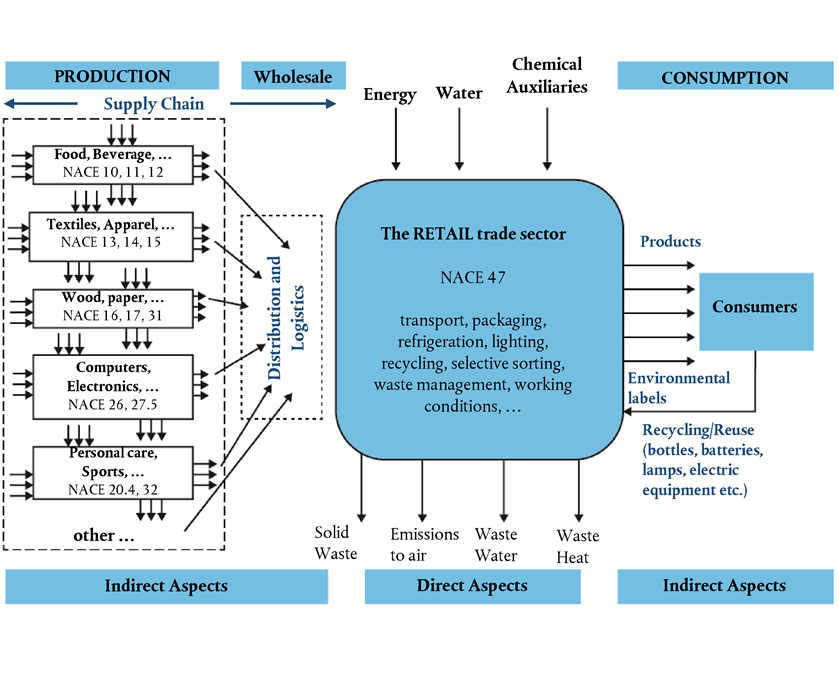

This SRD addresses the environmental management of retail trade sector organisations. This sector is characterised within the statistical classification of economic activities established by Regulation (EC) No 1893/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council(7) with NACE code 47 (NACE Rev. 2): ‘retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles’. Retailing of services, e.g. restaurants, hairdressers, travel agents are excluded.

It covers the whole value chain for the products sold in retail stores, as described in the following input/output scheme.

The main environmental aspects to be managed by the organisations belonging to the retail trade sector are set out in Table 2.1.

For each category, the table shows the aspects covered in this SRD. These environmental aspects were selected as the most relevant for retailers. However, the environmental aspects to be managed by specific retailers should be assessed on a case by case basis. Environmental aspects, such as waste water, hazardous waste, biodiversity or materials for other areas than those listed could also be relevant.

Table 2.1

Main environmental aspects covered in this document

| a This is an approximate classification of the nature of environmental aspects according to the definitions given in Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009. The direct or indirect nature of each environmental aspect should be assessed for each specific case. | ||

| b Those products manufactured by a company which are sold under another company's (e.g. a retailer's) brand. Own-brand products are also called private labels. | ||

| Category | Charactera | Aspects covered in this document |

|---|---|---|

| Energy performance | Direct | Building, Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning system (HVAC), refrigeration, lighting, appliances, renewable energy, energy monitoring |

| Air Emissions | Direct | Refrigerants |

| Supply Chain | Indirect | Business strategies, product prioritisation, improvement mechanisms, choice editing, environmental criteria, information and dissemination, environmental-labelling (including own-brand productsb) |

| Transport and logistics | Direct/Indirect | Monitoring, procurement, decision-making, transport modes, distribution network, planning, packaging design |

| Waste | Direct | Food waste, packaging, return systems |

| Materials and resources | Direct | Paper consumption |

| Water | Direct | Rainwater collection and treatment |

| Influence on consumers | Indirect | Environmental aspects associated with consumption, e.g. plastic bags |

Consequently, the ‘Best Environmental Management Practices (BEMPs)’ presented are grouped as follows:

BEMPs to improve the energy performance, including refrigerants management

BEMPs to improve the environmental sustainability of retail supply chains

BEMPs to improve transport and logistics operations

BEMPs concerning waste

other BEMPs (reduced consumption and use of more environmentally-friendly paper for commercial publications, rainwater collection and reuse, and influencing consumer environmental behaviour).

The BEMPs cover the most significant environmental aspects of the sector.

3.BEST ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES, SECTOR ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE INDICATORS AND BENCHMARKS OF EXCELLENCE FOR THE RETAIL TRADE SECTOR

3.1. Energy performance including refrigerants management

3.1.1. Design and retrofitting the building envelope for optimal energy performance

BEMP is to improve the envelope of existing retailers' buildings to minimise energy losses to an acceptable and feasible level, through the application of several techniques, such as those shown in Table 3.1. Moreover, BEMP is to optimise the building envelope design in order to fulfil demanding standards going beyond existing regulations, especially for new buildings.

Table 3.1

Building envelope elements and associated techniques

| Envelope element | Technique |

|---|---|

| Wall/façade/roof/floor — cellar ceiling | Change insulation materials |

| Techniques to increase the insulation thickness | |

| Windows/glazing | Change to more efficient glazing |

| Change to more efficient sashes and frames | |

| Shading | Use of external and internal shading devices |

| Air tightness | Improvement of doors |

| Fast acting doors | |

| Sealing | |

| Introduce buffer sections | |

| Overall envelope | Orientation |

| Maintenance |

Applicability

Technically, it is feasible for every new and existing building or building unit. Tenants may implement mechanisms to influence owners and should be aware of the importance of the building envelope in their environmental performance. Building envelope retrofitting requires significant investment. Generally, this BEMP produces cost savings, but with long payback times and, therefore, it is recommendable to apply this BEMP along with other major renovations of the store (e.g. store layout, lighting, safety, structural, extensions, etc.) in order to reduce its cost.

The applicability of this BEMP to small enterprises (8) is usually quite limited, due to the high investment needed and the lack of influence on the building characteristics.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

| a This benchmark can also be seen in the light of the Directive 2010/31/EU on the energy performance of buildings and the national definitions of nearly zero energy buildings (NZEB). An illustration/example of this is a threshold 20 kWh/m2yr (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0483). | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmark of excellence |

|---|---|

(i1)Specific energy use of the store per m2 (sales area) and year.(i2)Specific energy use of the store per m2 (sales area) and year in terms of primary energy. | (b1)Specific energy use per m2 of sales area for heating, cooling and air conditioning lower or equal to 0 kWh/m2yr if waste heat from refrigeration can be recovered. Otherwise, lower or equal to 40 kWh/m2yr for new buildings and 55 kWh/m2yr for existing buildingsa. |

3.1.2. Design premises for existing and new Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning systems

BEMP is to retrofit existing HVAC (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) systems in order to reduce energy consumption and improve indoor air quality. BEMP is to optimise the design of HVAC systems in new buildings, using innovative systems to reduce primary energy demand and to increase efficiency.

The application of best design practices should allow best integration within the building envelope, avoiding oversizing and using the orientation of the building as a way of minimising overall energy consumption. In particular, for new stores, the following may be relevant: the use of glazing, waste heat from refrigeration, renewable energy, heat pumps, and other innovative systems. Indoor air quality monitoring and energy management systems are considered best practices regarding HVAC maintenance.

Applicability

This BEMP is fully applicable to new buildings. In any existing building, the HVAC system can be retrofitted in order to reduce energy consumption, although building characteristics would have an influence on the impact of retrofitting the HVAC system. The climatic influence is very relevant in order to select what techniques can be implemented. The application of new HVAC systems in an existing building, e.g. the installation of cogeneration plants, heat recovery systems and integrated design concepts, such as the Passive House standard, can be applied partially with acceptable economic performance. The store layout has a strong influence on the performance of HVAC, especially those design specifications related to the refrigeration process, where a huge amount of waste heat can be recovered.

For small enterprises, the degree of influence on the HVAC design can be negligible, although they should participate in the implementation and recommendation of the described BEMP.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.1.3. Use of integrated design concepts for buildings

BEMP is to use integrated design concepts for the whole building or for parts of it to reduce the energy demand of the store. Integrated concepts minimise the energy use and associated costs of a building, while achieving good thermal comfort conditions for the occupants. Some exemplary requirements are shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2

Examples of requirements for integrated design concepts

| Requirements | Examples of measures to achieve them |

|---|---|

| The building energy need for space heating and cooling must be lower than 15 kWh/m2yr The specific heat load must not exceed 10 W/m2 The building must not leak more air than 0,6 times its volume per hour Total primary energy use cannot be higher than 120 kWh/m2yr | Improved insulation. Recommended U-values less than 0,15 W/m2K Design without thermal bridges Windows U-values lower than 0,85 W/m2K Air tight. Mechanical ventilation with heating recovery from exhaust air Install solar thermal systems or heat pumps (final energy demand excludes the contribution of solar and ambient energy used on site to produce heat) |

Applicability

Integrated concepts are usually implemented during the design of new buildings. The concept is partially suitable for existing buildings, as several elements can be integrated without high investment costs. The climatic conditions can also influence the decision to apply this concept. For example, the Passive House standard was mainly developed by German and Swedish researchers, but it may be implemented in warmer climates. The investment costs of a building designed according to exemplary integrated approaches do not exceed 10-15 % of extra cost compared to a conventional construction. The life cycle cost analysis reveals that the passive house building design represents the minimum life cycle cost, as the heating system required is relatively simple and the heating power installed is limited.

For small enterprises, the use of integrated design concepts to minimise energy demand of new buildings can be regarded as a cost-efficient procurement activity, without any specific restriction other than extra initial investment.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.1.4. Integration of refrigeration and HVAC

BEMP is to recover the waste heat from the refrigeration cycle and to maximise its use. Food retailers are able, under certain circumstances, to produce excess heat even after using the heat for space heating, which can be delivered to other parts of the same building or to other buildings.

Applicability

The measures should be taken into account for new or existing buildings of food retailers and the operation of these systems would have different results depending on different factors:

:

large retailers' stores are usually not alone in their buildings. Therefore, the ‘neighbourhood’ (e.g. small shops in a shopping centre) is a potential consumer of the excess heat. As a general rule, a grocery store with a typical refrigeration load and an optimised envelope would recover enough energy to heat twice its own surface.

:

all the elements of the HVAC system should be correctly designed and maintained. Exhaust air heat recovery, on-demand control of ventilation with CO2 sensors and monitoring of air tightness and indoor air quality are strongly recommended techniques.

:

smaller shops offer more refrigerated goods per square metre of sales area and the efficiency in refrigeration is lower. In addition, the trend to increase the amount of refrigerated goods available is also important. The size of the shop does not influence the technical applicability of integrated approaches, but the cost-efficiency of the whole system is lower for small shops.

:

in cold climates, the load for refrigeration is lower than for warmer regions. At the same time, the heat demand of northern European buildings is high, so the integration would depend on the quality of the building envelope. For the warmest climates, e.g. Mediterranean countries of Europe, the cooling demand can be very significant and the air tightness of the building can make the internal gains increase. An optimised ventilation design is, therefore, necessary. Mechanical cooling at night and variable indoor temperature (e.g. 21-26 °C) are also recommended techniques.

:

in the integration of the refrigeration cycle, there is a limit to ambient temperature, which depends on the system design, where the waste heat generation rate is not enough to keep a comfortable temperature inside the buildings. An extra heating source may be needed but this, again, depends on the quality of the building envelope.

:

many shops are integrated in a residential or commercial building, which belongs to a third party. Better integration of heat recovery, therefore, must involve actual building owners.

This BEMP is applicable to any new and existing refrigeration system to be installed in new or renovated stores, being fully applicable to small enterprises (given the conditions above). Nevertheless, small companies may require outsourcing technical assistance.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.1.5. Monitoring the energy performance of stores

BEMP is to monitor the energy use of the processes inside a store (at least of the most energy-consuming processes such as heating, refrigeration, lighting, etc.), as well as at store and/or organisation levels. Also, it is BEMP to benchmark the energy consumption (per process) and to implement preventive and corrective measures.

Applicability

A monitoring system can be applied to any sales concept. It requires the allocation of extra resources if there is not an appropriate business management structure. This practice may require extra efforts for existing stores.

Small enterprises managing one or a few stores may require a good business management structure and shared responsibility approaches to establish and maintain an appropriate monitoring system. There may be affordability problems for the application of this BEMP to existing stores.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

| a Note: under the Energy Efficiency Directive large enterprises have an obligation to undertake energy audits, carried out by qualified experts, every four years, the first by 5 December 2015. | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmarks of excellence |

|---|---|

(i4)Implementation of a monitoring system (y/n)(i5)Percentage of stores controlled(i6)Number of controlled processes | (b3)100 % of stores and processes are monitored and energy use figures are reported on an annual basis (based on the outcome of an annual energy audit)a.(b4)Benchmarking mechanisms implemented. |

3.1.6. Efficient refrigeration, including refrigerants use

BEMP is to implement energy-saving measures in the refrigeration system of a grocery store, especially the covering of refrigeration display cases with glass lids, when the energy-saving potential produces relevant environmental benefits.

BEMP is to use natural refrigerants in grocery stores, as the environmental impact would be reduced substantially, and to avoid leakages by ensuring that installations are tightly sealed and well maintained.

Applicability

This practice is applicable to food retailers with a significant load of refrigeration. Covering of cabinets can have short payback times (less than three years) when anticipated savings are equal to or higher than 20 %. Covering of display cases may also have an impact on the thermal behaviour of the store, as well as on the humidity of the indoor environment. In addition, the application of natural refrigerants, apart from the environmental benefit, may reduce the energy consumption under certain circumstances of food retailer operation.

The applicability to small enterprises may be restricted to organisations using commercial refrigeration systems, both plug-in and remote systems.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.1.7. Efficient lighting

BEMP is to design smart lighting strategies with enhanced efficiency and reduced consumption, to use daylight without affecting the sales concept and to use intelligent controls, appropriate system design and the most efficient lighting devices to ensure optimal lighting levels.

Applicability

This technique is applicable to any sales concept. Specific lighting for marketing purposes is also affected. However, the influence of increased glazing, allowing further use of day lighting, on the thermal balance of the store should be carefully considered. The definition of an optimal lighting strategy and using the most efficient devices can lead to savings higher than 50 % compared to current performance.

Use of smart lighting systems and efficient devices is feasible for small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

| a This benchmark should also be seen in light of the EU GPP criteria for retail indoor lighting, which is 3,5 W/m2/100 lux (core criteria) or 3,2 W/m2/100 lux (comprehensive criteria). See: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/criteria/indoor_lighting.pdf | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmark of excellence |

|---|---|

(i1)Specific energy use of the store per m2 sales area and year.(i10)Installed lighting power per m2. | (b9)Installed lighting power lower than 12 W/m2 for supermarkets and 30 W/m2 for specialist shopsa. |

3.1.8. Secondary measures for improving energy performance

BEMP is to implement energy saving measures in distribution centres, to audit energy use periodically within the environmental management system, to train staff regarding energy savings and to communicate the energy saving efforts of the organisation internally and externally.

Applicability

There is no limitation on the size, type or geographical location of the retailer to establish a comprehensive energy management system, taking into account appliances, distribution centres, specific energy uses or communication and training.

For small enterprises, procurement of efficient appliances, staff training and communication are feasible and affordable measures.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

| a The energy management system can be part of EMAS. | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmark of excellence |

|---|---|

(i1)Specific energy consumption of the store per m2 (sales area) and year.(i10)Installed lighting and/or appliance power per m2.(i11)Energy management systema in place to drive continuous improvement (y/n). | (b10)100 % of distribution centres who exclusively service the retailer are monitored. |

3.1.9. Use of alternative energy sources

After minimising the energy demand, BEMP is to integrate renewable energy sources in stores. Meeting the energy demand with renewable energy has substantial environmental benefits. However, it is crucial to first reduce the energy demand and increase the efficiency as explained in 3.1.1 to 3.1.8 and then integrate renewables for the remaining energy demand. The implementation of heat pumps and combined heat and power systems should also be considered.

Applicability

In principle, it is applicable to any store format. Important limitations are the availability of renewable sources, accessibility of land or roof installations and stability of demand for combined heat and power systems.

Green purchasing can be a good solution for micro enterprises. For small enterprises, the use of renewable energy or other alternative sources is achievable.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

| a Alternatively, on-site or nearby renewable energy ratio according to prEN15603. | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmark of excellence |

|---|---|

(i12)Specific on-site or nearby alternative energy generation per m2 of sales area per energy source.(i13)Percentage of renewable energy produced on-site or nearby, as a ratio of the energy use of the storea. | (b11)To have nearly zero energy buildings (stores or distribution centres) where local conditions allow the production of renewable energy on site or nearby. |

3.2. Retail supply chain

3.2.1. Integrate supply chain environmental sustainability into business strategy and operations

BEMP is for top-level management to integrate supply chain environmental sustainability into the business strategy, and for dedicated management personnel (ideally within a dedicated unit) to coordinate implementation of necessary actions across retail operations. Actions should at least be coordinated across individuals or departments responsible for procurement, manufacturing, quality assurance, transport and logistics, and marketing. The establishment of quantitative environmental sustainability targets that are widely communicated and highly weighted in the corporate decision-making process is particularly important, both as an indicator and driver of actions to improve supply chain environmental sustainability. A sequence of best practice actions for systematic improvement of product supply chains, determined according to chronological order and environment effectiveness, is proposed in Figure 3.1. BEMP is the implementation of this sequence of actions (also reflecting BEMPs described subsequently).

Applicability

Integration of an environmentally sustainable supply chain strategy into retail management structure and operations is possible for any retailer. For large retailers, this BEMP is more complex and requires extensive training and reorganisation to establish environmentally sustainable sourcing priorities. Integrating management of supply chain environmental sustainability into retail organisations can improve long-term economic performance, by creating a strong value-added brand identity, and by securing efficient and sustainable product supplies into the future.

For small enterprises, such actions may be relatively straight-forward to implement and may be associated with a change in market positioning to emphasise a more sustainable value-added product assortment.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.2.2. Assess core product supply chains to identify priority products, suppliers and improvement options and identify effective product supply chain improvement mechanisms

As per the sequence of BEMPs applicable to environmental improvement of retail supply chains (Figure 3.1), retailers should identify priority products, processes and suppliers for improvement through environmental assessment of product supply chains, using existing scientific information, consultation with experts (e.g. NGOs), and lifecycle assessment tools. Then, retailers must identify the relevant improvement options available for priority product groups. One important aspect of this is the identification of relevant widely-recognised third-party environmental standards that may be used to indicate higher levels of supplier and/or product environmental performance. The applicability and level of environmental protection represented by such standards vary considerably.

Some standards are widely applicable (Table 3.4 to Table 3.7) and best practice for them is ensuring that all suppliers/products are certified with them. The Energy Labelling Directive 2010/30/EU created a legal framework that allows consumers but also retailers to concentrate their product portfolio on the highest energy efficiency class. Other standards are not based on criteria that can be widely applied to improve the environmental sustainability of all products and suppliers, but instead seek to identify front-runner products (Table 3.3). For example, the EU Ecolabel is awarded to products that demonstrate lifecycle environmental performance equivalent to the top 10-20 % of products within the relevant category. Best practice for high requirement standards, such as ISO type-I environmental labels(9) and organic standards, is to promote their selection by consumers.

Table 3.3

Illustrative and non-exhaustive examples of front-runner ‘environmental product’ certification standards and product groups to which they apply

| a Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008 of 5 September 2008 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products with regard to organic production, labelling and control (OJ L 250, 18.9.2008, p. 1). | |

| b Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91 (OJ L 189, 20.7.2007, p. 1). | |

| Standard | Product groups |

|---|---|

| Blue Angel EU Ecolabel Nordic Swan EU Energy Labelling (highest efficiency class) | Non-food products |

| Organic (as per Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008a and Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007b). Includes GOTS, KRAV, Soil Association, BioSuisse, etc. | Food and natural fibre products |

For widely applicable standards, a simple classification scheme is proposed, using some commonly-used standards as examples. Table 3.4 details proposed criteria that standards would mandate to products and their manufacturing in order for such standards to be considered ‘basic’, ‘improved’ or ‘exemplary’.

Table 3.4

Proposed classification criteria for ‘basic’, ‘improved’ and ‘exemplary’ standards for products sold by retailers

| Basic | Improved | Exemplary |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Examples of basic, improved and exemplary environmental standards, and product groups to which they apply, are listed in Table 3.5, Table 3.6 and Table 3.7, respectively.

The Tables 3.5, 3.6, 3.7 and 3.8 contain illustrative and non-exhaustive examples that constitute no official endorsement of ‘basic’, ‘improved’ and ‘exemplary’ standards for product groups.

Table 3.5

Illustrative and non-exhaustive examples of ‘basic’ environmental standards and product groups to which they apply

| Standard | Product groups |

|---|---|

| GlobalGAP (Good Agricultural Practice) and benchmarked standards | Crops and livestock |

| Oeko-Tex 1000 | Textiles |

| National/regional production certification (e.g. Red Tractor British origin certification) | All products |

| Red-listed fish (deselection) | Fish |

Table 3.6

Illustrative and non-exhaustive examples of ‘improved’ environmental standards and initiatives and the product groups to which they apply

| Standards and initiatives | Product groups |

|---|---|

| BCI (Better Cotton Initiative) | Cotton products |

| BCRSP (Basel Criteria on Responsible Soy Production) | Soy (feed supporting dairy, egg and meat) |

| BSI (Better Sugarcane Initiative) | Sugar products |

| 4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community Association) | Coffee |

| Fair-trade | Agricultural products from developing regions |

| RA (Rainforest Alliance) | Agricultural products from tropics |

| RSPO (Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil) | Palm oil products |

| PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forestry Certification) | Wood and paper |

| RTRS (Round Table on Responsible Soy) | Soy (feed supporting dairy, egg and meat) |

| UTZ | Cocoa, coffee, palm oil, tea |

Table 3.7

Illustrative and non-exhaustive examples of ‘exemplary’ environmental standards and initiatives and the product groups to which they apply

| Standard | Product groups |

|---|---|

| FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) | Wood and paper |

| MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) | Wild-catch seafood |

Where widely-applicable environmental standards are not available, retailer best practice is to specify within contractual agreements environmental criteria that address supply chain environmental hotspots, or to intervene to improve supply chain performance through best practice dissemination and environmental performance benchmarking.

Applicability

Any retailer can identify the most effective supply chain improvement mechanisms. For large retailers with own-brand products, all aspects of this BEMP can be implemented.

For small enterprises, this technique is restricted to identification of priority products for choice editing or green procurement based on third-party certification. Implementation of a systematic and targeted approach over time does not entail significant expenditure.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.2.3. Choice editing and green procurement of priority product groups based on third party certification

BEMP is to exclude the most unsustainable products (e.g. endangered species), and require widespread (i.e. target of 100 % sales share) certification according to third party environmental standards for products that have been identified as priorities for environmental improvement. Environmental standards apply to products and/or suppliers, and are broadly classified as basic, improved or exemplary according to the rigour and comprehensiveness of environmental requirements (see Table 3.8 for illustrative and non-exhaustive examples). BEMP is to apply the highest level of widely-recognised environmental standard available.

Table 3.8

Illustrative and non-exhaustive examples of best practice underpinning benchmarks of excellence for this BEMP across product groups

| Product group | Best practice examples(actual or target sales shares for different standards) |

|---|---|

| Coffee, tea | 100 % Fair-trade; 100 % 4C |

| Fruit and vegetables | 100 % Global GAP |

| Fats and oils | 100 % RSPO; 100 % RTRS |

| Seafood | 100 % MSC |

| Sugar | 100 % Fair-trade |

| Textiles | 100 % BCI |

| Wood and paper | 100 % FSC |

Applicability

This BEMP applies to all retailers. The benchmark of excellence is expressed in relation to own-brand products sold by larger retailers.

Small enterprises without own-brand product ranges should avoid the most environmentally-damaging products (e.g. endangered species of fish) and stock branded products that have been certified according to relevant environmental standards (e.g. Table 3.3).

Third-party environmental standards may not cover all relevant environmental aspects and processes along the supply chain, and environmentally-rigorous, widely-applicable standards are not available for all product groups. Product groups not referred to in Table 3.8 may be targeted for supply chain improvement through the enforcement of product/supplier requirements, retailer intervention (e.g. supplier benchmarking) and the promotion of front-runner ‘eco products’, as described in subsequent BEMPs.

If environmental certification is specified as an ‘order qualifying’ criteria, compliance and certification costs are borne by suppliers and not passed on to retailers. However, best practice involves retailers providing support to existing suppliers to achieve certification, in which case costs are shared. For suppliers, compliance costs may be regarded as an investment to expand market acceptance of their products and possibly to implement price premiums. For retailers, additional costs associated with this technique may be balanced against supply chain risk reduction and potential pricing and marketing advantages.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.2.4. Enforce environmental requirements for suppliers of priority product groups

BEMP is to establish environmental criteria for priority products and their suppliers, targeting identified environmental hotspots, and to enforce compliance of these criteria through product and supplier auditing.

Applicability

This BEMP is applicable to large retailers and for own-brand priority products. Auditing of supplier environmental performance can be integrated into social auditing and product quality control systems to minimise additional costs. For suppliers, compliance costs may be balanced against improved security of demand and enhanced marketability for their products, and any price premiums they may consequently realise. For retailers, costs may be balanced against reduced reputational and medium-term business supply chain risks associated with unsustainable practices, and against price and marketing premiums they may consequently realise.

This BEMP is not applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.2.5. Drive supplier performance improvement through benchmarking and best practice dissemination

BEMP is to drive supplier improvement by establishing information exchange systems that can be used to benchmark suppliers, and by disseminating better management practices. The latter aspect may assist supplier compliance with third party standards and retailer-defined criteria.

Applicability

This BEMP is applicable to large retailers and for own-brand priority products. Retailers may offer suppliers a small price premium to encourage participation in improvement schemes, and pay for data collation and dissemination of better management practice techniques. These costs should be balanced against reduced reputational and medium-term business supply chain risks associated with unsustainable practices, and against price premiums that retailers may consequently implement. The dividends of any identified efficiency improvements may be shared with retailers through contractual agreement.

This BEMP is not applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.2.6. Collaborative research and development to drive widespread supply chain improvement and innovation

BEMP is to strategically collaborate with other stakeholders to identify and develop innovative supply chain improvement options, and to develop widely accepted environmental standards.

Applicability

Any large retailer with own-brand supply chains can collaborate with research institutes or consultancies to improve supply chain sustainability. Retailers may want to focus such research and development on product groups for which there are no existing commercially viable and widely applicable improvement options. This practice can be regarded as an investment in securing sustainable and economically competitive supply chains.

This BEMP is not applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.2.7. Promote front-runner ecological products

BEMP is to promote front-runner certified ecological products. Awareness campaigns, sourcing, pricing, in-store positioning and advertising are important components of this technique, which can be effectively implemented through development of own-brand ecological ranges.

Applicability

All retailers can stock and encourage consumption of front-runner ecological products. Large retailers can implement this technique more extensively, through the development of own-brand ecological ranges. Supplier costs associated with front-runner certification may be passed on to retailers. Certified front-runner ecological products are associated with significant price premiums and higher profit margins. Own-brand ecological ranges are also likely to increase a retailer's overall own-brand product sales through a positive ‘halo effect’.

This BEMP is applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.3. Transport and logistics

3.3.1. Green procurement and environmental requirements for transport providers

BEMP is to integrate environmental performance and reporting criteria into the procurement of transport and logistics services provided by third parties, including requirements for implementation of BEMPs described in this document.

Applicability

All retailers purchase at least part of their transport and logistics operations from third party providers, and can make purchasing decisions according to efficiency or environmental criteria. Nevertheless, improving the efficiency of transport and logistics operations reduces operating costs, and requires effective monitoring and reporting. Efficient third party transport providers may be able to offer lower cost services to retailers.

Small retailers are usually dependent on third party providers.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.3.2. Efficiency monitoring and reporting for all transport and logistics operations

BEMP is to report on the efficiency and environmental performance of all transport and logistics operations between first-tier suppliers, distribution centres, retailers and waste management facilities, based on monitoring of in-house operations and data provided by third party operations.

Applicability

This practice is applicable by all retailers. Reporting on in-house transport and logistics operations will only apply to larger retailers. Effective monitoring and reporting requires small investment in necessary information technology systems and management but can identify options to improve the efficiency of transport and logistics operations.

For small enterprises, basic data on average emission factors for different modes of transport are available to estimate emissions.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.3.3. Integrate transport efficiency into sourcing decisions and packaging design

BEMP is to integrate transport efficiency into sourcing decisions and packaging design, based on life cycle assessment of products sourced from different regions, and through designing product packaging to maximise the density of transport units.

Applicability

This practice is applicable to large retailers with own-brand ranges. It is highly dependent on product and source location, related to a multitude of sourcing factors. For packaging, increasing the density of packaged goods can considerably improve transport efficiency and therefore reduce transport costs.

This BEMP is not applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.3.4. Shift towards more efficient transport modes

BEMP is to shift towards more efficient transport modes, especially rail, water-based transport and larger trucks, and to minimise air-freight, for as much of the transport distance as possible. The possibility to make such shifts may be limited to primary distribution, from supplier distribution centres (DCs) to retailer DCs, given that the first and final kms often necessitate road transport. Modal shifts therefore require optimisation of distribution networks to accommodate intermodal transfers (e.g. siting distribution centres with access to rail and water networks). Shifting from smaller to larger trucks, including trucks with double-deck trailers, is included in this technique owing to the considerably greater efficiency of large compared with small trucks. Modal shifts may also inform product sourcing decisions where transport represents a significant component of product lifecycle environmental impacts (considering all relevant lifecycle implications).

Table 3.9

Ranking of transport modes in order of environmental preference (highest first)

| Ranking | Transport mode |

|---|---|

| 1 | Freight train |

| 2 | Ocean ship |

| 3 | Inland waterway |

| 4 | Large truck |

| 5 | Medium truck |

| 6 | Small truck |

| 7 | Air freight |

Applicability

All retailers can take action to shift product transport onto less polluting modes, at least based on vehicle size, and most large retailers can shift at least some primary distribution from road to rail or water. However, achieving large-scale shifts in retail goods transport from road to rail and inland waterways will require improvements in national rail and waterway infrastructures and greater cross-border coordination by operating companies. Therefore, national transport infrastructure and policy (e.g. road pricing) can have a significant influence on retailers' scope for improvement and decision-making regarding transport mode.

It is not applicable to small enterprises, except where available procurement choices enable selection of more efficient transport modes for particular products.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.3.5. Optimise the distribution network

BEMP is to optimise the distribution network through the systematic implementation of the most efficient of the following options: (i) strategic centralised hubs to accommodate rail and water-based transport, (ii) consolidated platforms, (iii) and direct routing.

Applicability

This is applicable to large retailers with in-house transport and logistics services and for third party transport providers, especially when products are sourced over longer distances. This practice does not require significant investment. Building new central hubs integrated with rail and water-based transport networks does require significant investment. In both cases, increased loading efficiency and the use of more efficient modes for longer distance routes can significantly reduce operating costs.

It is not applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.3.6. Optimise route planning, use of telematics and driver training

BEMP is to optimise operational efficiency through efficient route planning, use of telematics, and driver training. Efficient route planning includes back-loading store delivery vehicles with waste and with supplier deliveries to distribution centres, and making night deliveries to avoid traffic congestion.

Applicability

This is applicable to all products to be supplied to large retailers with in-house transport and logistics services, and for third party transport providers. Driver training usually produces savings of 5 % of fuel. Route optimisation may require significant investment in information technology, but can reduce capital investment costs (fewer trucks required) and significantly reduce operating (fuel) costs.

It is applicable to small enterprises if they have their own transport vehicles (e.g. delivery vans).

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.3.7. Minimise the environmental impact of road vehicles through purchasing decisions and retrofit modifications

BEMP is to minimise the environmental impact of road vehicles through purchasing choices and retrofit modifications. This includes the purchase of alternatively powered vehicles, efficient and low-pollution vehicles and low-noise vehicles, aerodynamic modifications, and the application of low rolling resistance tyres.

Applicability

This is applicable for all products to be supplied to large retailers with in-house transport and logistics services, and for third party transport providers. For vehicles driven long distances at higher speeds (> 80 km/h), small investments in aerodynamic modifications and larger investments to upgrade to more aerodynamic tractor and trailer units offer payback periods of up to two years. The same payback time periods apply to installing low rolling resistance tyres. Alternatively-powered vehicles require considerably higher investment costs.

It is applicable to small enterprises if they have their own transport vehicles (e.g. delivery vans).

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

| a EURO VI standard for vehicle emissions entered into force at the end of 2012, therefore it may be considered as benchmark of excellence in the future years. | |

| Environmental performance indicators | Benchmarks of excellence |

|---|---|

(i56)l/100 km (vehicle fuel consumption) or kg CO2 eq. per tkm.(i57)Percentage vehicles within transport fleet compliant with different EURO classes.(i58)Percentage of vehicles, trailers and loading equipment compliant with PIEK noise standards, or equivalent standards that enable night deliveries.(i59)Percentage of vehicles in transport fleet powered by alternative fuel sources, including natural gas, biogas, or electricity.(i60)Percentage of vehicles within transport fleet fitted with low rolling resistance tyres.(i61)Percentage of vehicles and trailers within transport fleet designed or modified to improve aerodynamic performance. | (b30)100 % trucks EURO Va compliant and with HGV fuel consumption of less than 30 l/100 km.(b31)100 % trucks, trailers and loading equipment compliant with PIEK noise standards, or equivalent standards that enable night deliveries.(b32)Operation of alternatively fuelled vehicles (natural gas, biogas, electric).(b33)100 % vehicles fitted with low rolling resistant tyres.(b34)100 % vehicles and trailers designed or modified to improve aerodynamic performance. |

3.4. Waste management

3.4.1. Food waste minimization

BEMP is to integrate environmentally friendly practices to avoid food waste generation, such as monitoring, auditing, prioritising, logistic issues, better preservation mechanisms, in-store temperature and humidity control, distribution centres and delivery trucks, staff training, donation, advice to consumers, etc. and to avoid landfilling or incineration of food waste through fermentation processes.

Applicability

This is a cost-efficient measure, applicable to food retailers of any size and in any Member State. However, policies may be in place to avoid/discourage food donation.

All small enterprises can apply preventive measures to avoid food waste generation. Management costs would be compensated by cost savings derived from less product losses and less generated waste.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmark of excellence

3.4.2. Integration of waste management in retailers activities

BEMP is to integrate waste management practices where prevention is prioritised. Best practices include:

In-house management practices:

segregated collection and specific treatment for reuse: compacting, briquetting for paper and plastic wastes, refrigeration of food wastes, etc.

monitoring of waste production

preparation for reuse of packaging materials, as pallets and plastic boxes for suppliers, distribution centres, showcases in stores and home delivery

staff training.

Organisation management practices:

monitoring of waste generated by stores per category and per final destination

implementation of reverse logistics for the management of packaging materials (to be reused or recycled), WEEE and other wastes (such as hazardous wastes) to suppliers, treatment facilities and/or distribution centres

establishment of local and/or regional partnerships for the management of wastes

communication to consumers of responsible management of waste at households.

Applicability

The described techniques are applicable to any retailer. Best practices should be suitable to retailers managing a significant number of stores and distribution centres. The allocation of resources to the effective reduction of waste would be economically justified. Bulk transportation back to distribution centres would allow the reduction of the treatment cost if it is compared to the costs negotiated at local or store level.

Small enterprises producing a huge amount of wastes should allocate resources and train staff in good waste management practices.

Associated environmental performance indicator and benchmark of excellence

3.4.3. Return systems for PET and PE bottles and for used products

BEMP is to implement take-back systems and to integrate them in the company logistics, as, for example, for PET or PE bottles.

Applicability

Food retailers, especially large chains, can implement this BEMP. It needs the allocation of resources, maintenance and equipment. In some countries it is already mandatory (e.g. Netherlands, Sweden and Germany).

For small enterprises, it requires extra resources for the daily operation of the return system.

Associated environmental performance indicator and benchmark of excellence

3.5. Use of less and certified/recycled paper for publications

BEMP is to reduce the impact through a decrease in the consumption of materials, such as paper optimisation for commercial publications, or the use of more environmentally friendly paper.

Applicability

All retailers, especially large chains producing huge amounts of printed commercial publications, can benefit from the implementation of this BEMP. A well implemented practice to reduce paper consumption can lead to cost savings.

This BEMP is applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicators and benchmarks of excellence

3.6. Rainwater collection and reuse

BEMP is to collect and reuse and/or infiltrate on site rainwater from roofs and parking areas.

Applicability

Retailers owning their own buildings and/or parking areas and in sites with the right conditions can implement this practice. Climatic conditions and standard rainwater collection system in the municipality can affect the application of this technique. It is a cost intensive measure.

This BEMP is applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicator and benchmark of excellence

3.7. Prevention of single-use plastic bags or other measures to influence consumer behaviour

BEMP is to influence consumers to reduce their environmental impact, through campaigns, such as the removal of plastic bags, responsible advertising and providing best guidance information to consumers.

Applicability

All retailers can implement this practice. Usually, regulations are the main drivers for their implementation.

This BEMP is applicable to small enterprises.

Associated environmental performance indicator and benchmark of excellence

4.RECOMMENDED SECTOR SPECIFIC KEY ENVIRONMENTAL INDICATORS

The scientific and policy report is publicly available on the JRC/IPTS website at the following address: http://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/activities/emas/documents/RetailTradeSector.pdf The conclusions on best environmental management practices and their applicability as well as the identified specific environmental performance indicators and the benchmarks of excellence contained in this Sectoral Reference Document are based on the findings documented in the scientific and policy report. All the background information and technical details can be found there.

Council Regulation (EEC) No 1836/93 of 29 June 1993 allowing voluntary participation by companies in the industrial sector in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (OJ L 168, 10.7.1993, p. 1).

Regulation (EC) No 761/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 March 2001 allowing voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS) (OJ L 114, 24.4.2001, p. 1).

Commission Decision 2013/131/EU of 4 March 2013 establishing the user's guide setting out the steps needed to participate in EMAS, under Regulation (EC) No 1221/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the voluntary participation by organisations in a Community eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS) (OJ L 76, 19.3.2013, p. 1).

Regulation (EC) No 1893/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 establishing the statistical classification of economic activities NACE Revision 2 and amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 3037/90 as well as certain EC Regulations on specific statistical domains (OJ L 393, 30.12.2006, p. 1).

A small enterprise is defined as an enterprise which employs fewer than 50 persons and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 10 million (Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (OJ L 124, 20.5.2003, p. 36)).

Type-I environmental labels: Third Party Certified Environmental Labelling (ISO 14024).

Options/Help

Print Options

PrintThe Whole Decision

You have chosen to open the Whole Decision

The Whole Decision you have selected contains over 200 provisions and might take some time to download. You may also experience some issues with your browser, such as an alert box that a script is taking a long time to run.

Would you like to continue?

You have chosen to open Schedules only

Y Rhestrau you have selected contains over 200 provisions and might take some time to download. You may also experience some issues with your browser, such as an alert box that a script is taking a long time to run.

Would you like to continue?

Mae deddfwriaeth ar gael mewn fersiynau gwahanol:

Y Diweddaraf sydd Ar Gael (diwygiedig):Y fersiwn ddiweddaraf sydd ar gael o’r ddeddfwriaeth yn cynnwys newidiadau a wnaed gan ddeddfwriaeth ddilynol ac wedi eu gweithredu gan ein tîm golygyddol. Gellir gweld y newidiadau nad ydym wedi eu gweithredu i’r testun eto yn yr ardal ‘Newidiadau i Ddeddfwriaeth’.

Gwreiddiol (Fel y’i mabwysiadwyd gan yr UE): Mae'r wreiddiol version of the legislation as it stood when it was first adopted in the EU. No changes have been applied to the text.

Rhagor o Adnoddau

Gallwch wneud defnydd o ddogfennau atodol hanfodol a gwybodaeth ar gyfer yr eitem ddeddfwriaeth o’r tab hwn. Yn ddibynnol ar yr eitem ddeddfwriaeth sydd i’w gweld, gallai hyn gynnwys:

- y PDF print gwreiddiol y fel adopted version that was used for the EU Official Journal

- rhestr o newidiadau a wnaed gan a/neu yn effeithio ar yr eitem hon o ddeddfwriaeth

- pob fformat o’r holl ddogfennau cysylltiedig

- slipiau cywiro

- dolenni i ddeddfwriaeth gysylltiedig ac adnoddau gwybodaeth eraill

Rhagor o Adnoddau

Defnyddiwch y ddewislen hon i agor dogfennau hanfodol sy’n cyd-fynd â’r ddeddfwriaeth a gwybodaeth am yr eitem hon o ddeddfwriaeth. Gan ddibynnu ar yr eitem o ddeddfwriaeth sy’n cael ei gweld gall hyn gynnwys:

- y PDF print gwreiddiol y fel adopted fersiwn a ddefnyddiwyd am y copi print

- slipiau cywiro

liciwch ‘Gweld Mwy’ neu ddewis ‘Rhagor o Adnoddau’ am wybodaeth ychwanegol gan gynnwys

- rhestr o newidiadau a wnaed gan a/neu yn effeithio ar yr eitem hon o ddeddfwriaeth

- manylion rhoi grym a newid cyffredinol

- pob fformat o’r holl ddogfennau cysylltiedig

- dolenni i ddeddfwriaeth gysylltiedig ac adnoddau gwybodaeth eraill

The data on this page is available in the alternative data formats listed: